Triplex: the Advent of Three Weekly Options Expirations

Justifying the existence of option liquidity premia on short tenor index options

By Arthur Wayne

January 21, 2021

Corn Cobs and the Option Illiquidity Premia

A widely accepted proxy for measuring option liquidity is the effective spread, the difference between the NBBO (national best bid-offer) and the price at which the end-user transacts at. Due to the idiosyncratic risks derivatives carry, options are generally less liquid and have larger effective spreads than their equities counterparts. Christoffersen et al. (2018) demonstrate the prevalence of larger effective spreads on S&P 500 single name options from 2004-2012. Increased end-user costs as a result of larger effective spreads—and therefore illiquidity—are referred to as ‘option illiquidity premia.’ These permia exist as a means for compensating market makers for accepting the costs of high-frequency hedging, managing inventory, and accounting for asymmetric information and certain unhedgeable risks (Christoffersen et al. 2018; Garleanu et al. 2008).

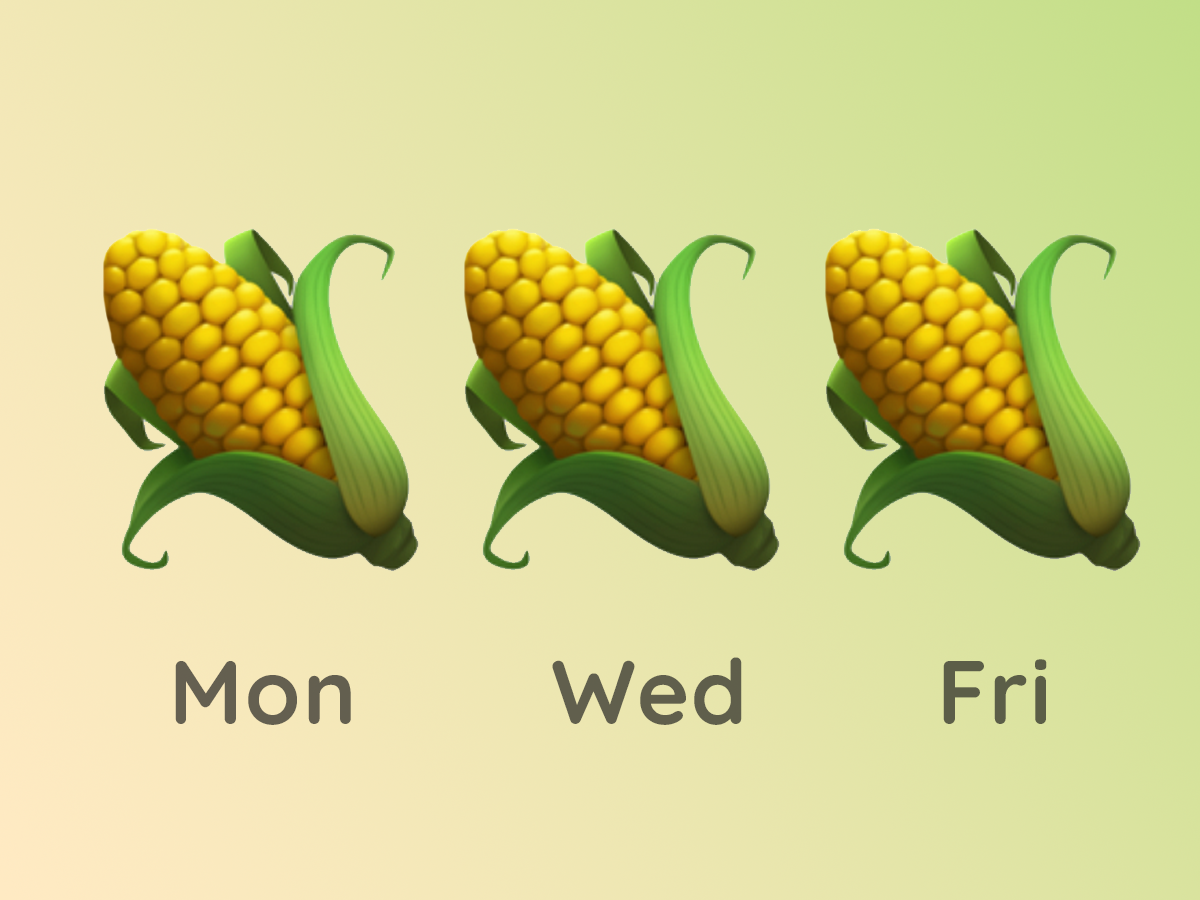

However, illiquidity in options markets may not always imply illiquidity premia. Unlike with other asset classes, derivatives markets are zero net supply markets. By contrast, commodities like corn have positive net supply: the tangible good of corn is constantly being grown for our purchase and consumption. But options are not corn, and options transactions are offsetting, so that parties directly exchange profits and losses with one another (See Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

The attribute of zero net supply therefore makes options markets heavily influenced by underlying demand dynamics. Li and Zhang (2011) find in zero net supply derivatives markets, the sign of illiquidity premia is a function of net demand. When end-users are net sellers, forcing market makers net long, the correlation between illiquidity and market maker expected returns is positive and demonstrates positive illiquidity premia. This correlation and the sign of illiquidity premia turns negative when end-users are net buyers (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Si denotes the sign of illiquidity premia and Sd denotes the sign of net demand

For the options markets on S&P 500 companies, intraday regression data between effective spreads and delta-hedged market maker returns indicates that illiquidity premia are positive and significant, implying that individual U.S. options markets are a net seller’s environment (Christoffersen et al. 2018). Thus, a significant portion of U.S. equity options prices are quoted at an illiquidity premia so that when general end-users sell-to-open their positions, they pay upfront costs via larger effective spreads.

The King of Liquidity

Enter SPY, the SPDR S&P 500 ETF. Also dubbed “The King of Liquidity,” SPY has the most liquid market of any stock or ETF, trading over $18 billion of notional value on a daily basis (Crigger 2019). Because of this, effective spreads on SPY stock or options are only pennies or sub-pennies wide. In normal market conditions, SPY enables traders to circumvent illiquidity premia simply due to its provision of immense liquidity. SPY’s unmatched liquidity notably provides end-users with the unique offering of three options expirations per week: on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays (excluding holiday weeks). We will refer to this phenomenon as ‘Triplex’, as in triple-expiration.

To provide some color into the recency and rarity of the Triplex phenomenon, the inception of exchange-traded options occurred in 1973, and there are currently over 5000 optionable tickers (CBOE 1). Of the optionable ticker universe, a small subset of names offers Friday Weekly options. Friday Weeklies were introduced in 2005 and are currently offered on 601 tickers (CBOE 2). Of the tickers offering Friday Weekly options, there exists an even smaller subset of less than 10 (index-tracking) tickers that offer Triplex—three weekly option expirations on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. As part of expanding the ‘Short Term Options Series program,’ SPY options expiring on Wednesday were added in 2016, and SPY options expiring on Monday were added in 2018. The purpose of these additions was to enable “greater trading and hedging opportunities and flexibility, and…provide customers with the ability to tailor their investment objectives more effectively” (SEC 1, SEC 2).

At face value, Triplex on index-tracking names makes sense because there is larger institutional demand to hedge against macroeconomic risk as opposed to single company risk. However, Triplex exposes a novel willingness of market makers to accept the unique risks of providing additional liquidity through middle-of-the-week expiration dates on index-tracking names, and more peculiarly, a willingness to provide even more liquidity on the Liquidity King, SPY. So why are market makers so eager to provide SPY’s option liquidity as opposed to the thousands of other optionable names? The answer lies in end-user demand dynamics for Weekly options.

Weekly Options Demand and Implied Jump Tail Risk

Research on short tenor options, like those offered by Triplex, is limited due to their recent inception. Available data, however, provide evidence that Weeklies have become the most heavily traded maturity class on index-tracking options. For SPX options (the older non-ETF, cash-settled brother of SPY), this is the case (See Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.3 from Andersen, Fusari, and Todorov (2017): Weekly volume % of all SPX option Volume is depicted by the gray line.

For market makers, Weekly options are attractive because of their short lifespan and therefore lower delta-hedging costs. For the end-user, Weeklies can act as inexpensive hedging instruments relative to their longer tenor counterparts. Investors can hedge immediate-term risks without paying inflated time-value premiums due to short-term jumps in implied volatility.

Andersen, Fusari, and Todorov (2017) challenge traditional arbitrage-free asset pricing models by using nonparametric modeling on Weekly option implied risk to prove that priced-in jump tail risk is a distinct variable from market volatility for calculating options prices. They call this variable Negative Tail Jump Variation (NTJV). When comparing a traditional parametric model deriving the NTJV from medium tenor options between 10 and 45 DTE (days-till-expiration) with their own nonparametric model deriving the NTJV from short tenor options up to 9 DTE, they find that during periods of elevated tail risk, the traditional parametric model outputs systemic mispricing errors (See Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.4, from Andersen, Fusari, and Todorov (2017): Top Panel: y-axis is NTJV estimates. The darker plotted line depicts the results from the nonparametric model and the lighter shaded line depicts results from the parametric model. The shading represents the difference between the two. Bottom Panel: y-axis is Z-scores of the degree of mispricing of OTM (out-of-the-money) puts from the traditional parametric model alone. The shaded area represents Z-scores above 2.5.

Evident in the bottom panel of Figure 1.3, the traditional parametric model consistently misprices OTM put options with Z-scores commonly reaching above 10 and even 20 at one point. They find that the correlation between the shaded areas on both top and bottom panels—the top panel representing the NJTV estimate difference and the bottom representing severe options mispricing—is high, at r = 0.46. Thus, an accurate option pricing model, especially one for short tenor options, must account for negative jump tail risk through NJTV as it is a significant and distinct variable from market volatility which is already factored into traditional arbitrage-free models. While the authors note that they lack the empirical data to explain the underlying economic reasons for NJTV’s significance, carrying over previous assumptions about option market demand dynamics may provide economic explanatory power.

Recall that because option markets are zero net supply markets, they are driven primarily by demand dynamics. In negative net demand markets like individual U.S. Equity Options, Li and Zhang (2011) demonstrate that the sign for illiquidity premia is positive. In these markets, market makers are net long and generate positive expected return by quoting a larger effective spread which forces net-selling end-users to accept the cost of selling options for less than full value. However, in a positive net demand market, because market makers are net sellers, the correlation between illiquidity and expected returns becomes negative, implying the existence of illiquidity discount—or in other words a liquidity premia. Liquidity premia create tighter effective spreads but also imply elevated options prices so that end-users, who are net buyers, compensate market makers for accepting the risks of being net option sellers.

When Andersen, Fusari, and Todorov (2017) found a large and consistent difference in accuracy for short tenor option pricing between a model which incorporates implied tail risk jumps and one that does not, they discovered evidence of liquidity premia on Weekly options and thus SPY Triplex options. The end-users of SPY Triplex options are net buyers who desire to reap the main benefit of short tenor options: cheaper tail risk hedging. Market makers very willingly accept the provision of Triplex on SPY because they understand that these contracts are in net positive demand for specifically hedging short-term tail risk, and so they embed the implied tail risk jump distribution into option liquidity premia. The main difference between offering only Weeklies (which were the subject of the Andersen, Fusari, and Todorov study) and offering Triplex is that in environments with immense liquidity like SPY’s, the addition of Monday and Wednesday expirations grants market makers even cheaper delta-hedging costs due to shorter lifespan, and market makers simply have more opportunities to make markets and thereby generate revenue. Because Triplex also benefits end-users by granting more flexibility and precision in creating complex hedges, it’s a win-win situation—but not without cost. The price the end-users must pay for Triplex is the liquidity premia.

Conclusion

Options carry intricate risks that no other financial instruments do, and as such, market-makers are compensated for providing option liquidity by enforcing either illiquidity premia or liquidity premia, depending on the sign of net demand within the given option market. Unlike within most US equity option markets, SPY Triplex options possess liquidity premia due to their heavy use as flexible and liquid hedging instruments. Triplex on SPY can be seen as a rare instance of the overprovision of liquidity in options markets in which liquidity premia is arbitrageable by means of short-term gamma collection, thus emulating the positioning and positive expected return of market makers. However, continued future research must be done on the Triplex phenomenon. Research on short tenor options in general is extremely sparse, but the literature will expand as additional expirations are gradually implemented onto other index-tracking names, and then eventually, non-index-tracking names, in the hopes of creating more complete and efficient options markets. When these events occur, there will be sufficient empirical data to test the validity of liquidity premia on all names that provide Triplex.

References

Andersen, Torben G., Nicola Fusari, and Viktor Todorov. "Short‐term market risks

implied by weekly options." The Journal of Finance 72.3 (2017): 1335-1386.

Chicago Board Options Exchange [1]. “Cboe History.” CBOE.com.

Chicago Board Options Exchange [2]. “Cboe Symbol Dir Weekly Options.” CBOE.com.

Christoffersen, Peter, et al. "Illiquidity Premia in the Equity Options Market." The

Review of Financial Studies 31.3 (2018): 811-851.

Crigger, Lara. "Why ‘SPY’ Is King Of Liquidity.” ETF.com, April 08, 2019.

Garleanu, Nicolae, Lasse Heje Pedersen, and Allen M. Poteshman. "Demand-based

Option Pricing." The Review of Financial Studies 22.10 (2008): 4259-4299.

Li, Gang, and Chu Zhang. "Why are derivative warrants more expensive than

options? An empirical study." Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis

(2011): 275-297.

Securities and Exchange Commission [1]. “Notice of Filing and Immediate

Effectiveness of Proposed Rule Change to Expand the Short Term Option Series Program.” Release No. 34-78695; File No. SR-NASDAQ-2016-122, August 26, 2016.

Securities and Exchange Commission [2]. “Notice of Filing and Immediate

Effectiveness of Proposed Rule Change to Expand the Short Term Option Series Program.” Release No. 34-82700; File No. SR-ISE-2018-13, February 13, 2018.

Corn Cobs and the Option Illiquidity Premia

A widely accepted proxy for measuring option liquidity is the effective spread, the difference between the NBBO (national best bid-offer) and the price at which the end-user transacts at. Due to the idiosyncratic risks derivatives carry, options are generally less liquid and have larger effective spreads than their equities counterparts. Christoffersen et al. (2018) demonstrate the prevalence of larger effective spreads on S&P 500 single name options from 2004-2012. Increased end-user costs as a result of larger effective spreads—and therefore illiquidity—are referred to as ‘option illiquidity premia.’ These permia exist as a means for compensating market makers for accepting the costs of high-frequency hedging, managing inventory, and accounting for asymmetric information and certain unhedgeable risks (Christoffersen et al. 2018; Garleanu et al. 2008).

However, illiquidity in options markets may not always imply illiquidity premia. Unlike with other asset classes, derivatives markets are zero net supply markets. By contrast, commodities like corn have positive net supply: the tangible good of corn is constantly being grown for our purchase and consumption. But options are not corn, and options transactions are offsetting, so that parties directly exchange profits and losses with one another (See Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

The attribute of zero net supply therefore makes options markets heavily influenced by underlying demand dynamics. Li and Zhang (2011) find in zero net supply derivatives markets, the sign of illiquidity premia is a function of net demand. When end-users are net sellers, forcing market makers net long, the correlation between illiquidity and market maker expected returns is positive and demonstrates positive illiquidity premia. This correlation and the sign of illiquidity premia turns negative when end-users are net buyers (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Si denotes the sign of illiquidity premia and Sd denotes the sign of net demand

For the options markets on S&P 500 companies, intraday regression data between effective spreads and delta-hedged market maker returns indicates that illiquidity premia are positive and significant, implying that individual U.S. options markets are a net seller’s environment (Christoffersen et al. 2018). Thus, a significant portion of U.S. equity options prices are quoted at an illiquidity premia so that when general end-users sell-to-open their positions, they pay upfront costs via larger effective spreads.

The King of Liquidity

Enter SPY, the SPDR S&P 500 ETF. Also dubbed “The King of Liquidity,” SPY has the most liquid market of any stock or ETF, trading over $18 billion of notional value on a daily basis (Crigger 2019). Because of this, effective spreads on SPY stock or options are only pennies or sub-pennies wide. In normal market conditions, SPY enables traders to circumvent illiquidity premia simply due to its provision of immense liquidity. SPY’s unmatched liquidity notably provides end-users with the unique offering of three options expirations per week: on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays (excluding holiday weeks). We will refer to this phenomenon as ‘Triplex’, as in triple-expiration.

To provide some color into the recency and rarity of the Triplex phenomenon, the inception of exchange-traded options occurred in 1973, and there are currently over 5000 optionable tickers (CBOE 1). Of the optionable ticker universe, a small subset of names offers Friday Weekly options. Friday Weeklies were introduced in 2005 and are currently offered on 601 tickers (CBOE 2). Of the tickers offering Friday Weekly options, there exists an even smaller subset of less than 10 (index-tracking) tickers that offer Triplex—three weekly option expirations on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. As part of expanding the ‘Short Term Options Series program,’ SPY options expiring on Wednesday were added in 2016, and SPY options expiring on Monday were added in 2018. The purpose of these additions was to enable “greater trading and hedging opportunities and flexibility, and…provide customers with the ability to tailor their investment objectives more effectively” (SEC 1, SEC 2).

At face value, Triplex on index-tracking names makes sense because there is larger institutional demand to hedge against macroeconomic risk as opposed to single company risk. However, Triplex exposes a novel willingness of market makers to accept the unique risks of providing additional liquidity through middle-of-the-week expiration dates on index-tracking names, and more peculiarly, a willingness to provide even more liquidity on the Liquidity King, SPY. So why are market makers so eager to provide SPY’s option liquidity as opposed to the thousands of other optionable names? The answer lies in end-user demand dynamics for Weekly options.

Weekly Options Demand and Implied Jump Tail Risk

Research on short tenor options, like those offered by Triplex, is limited due to their recent inception. Available data, however, provide evidence that Weeklies have become the most heavily traded maturity class on index-tracking options. For SPX options (the older non-ETF, cash-settled brother of SPY), this is the case (See Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.3 from Andersen, Fusari, and Todorov (2017): Weekly volume % of all SPX option Volume is depicted by the gray line.

For market makers, Weekly options are attractive because of their short lifespan and therefore lower delta-hedging costs. For the end-user, Weeklies can act as inexpensive hedging instruments relative to their longer tenor counterparts. Investors can hedge immediate-term risks without paying inflated time-value premiums due to short-term jumps in implied volatility.

Andersen, Fusari, and Todorov (2017) challenge traditional arbitrage-free asset pricing models by using nonparametric modeling on Weekly option implied risk to prove that priced-in jump tail risk is a distinct variable from market volatility for calculating options prices. They call this variable Negative Tail Jump Variation (NTJV). When comparing a traditional parametric model deriving the NTJV from medium tenor options between 10 and 45 DTE (days-till-expiration) with their own nonparametric model deriving the NTJV from short tenor options up to 9 DTE, they find that during periods of elevated tail risk, the traditional parametric model outputs systemic mispricing errors (See Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.4, from Andersen, Fusari, and Todorov (2017): Top Panel: y-axis is NTJV estimates. The darker plotted line depicts the results from the nonparametric model and the lighter shaded line depicts results from the parametric model. The shading represents the difference between the two. Bottom Panel: y-axis is Z-scores of the degree of mispricing of OTM (out-of-the-money) puts from the traditional parametric model alone. The shaded area represents Z-scores above 2.5.

Evident in the bottom panel of Figure 1.3, the traditional parametric model consistently misprices OTM put options with Z-scores commonly reaching above 10 and even 20 at one point. They find that the correlation between the shaded areas on both top and bottom panels—the top panel representing the NJTV estimate difference and the bottom representing severe options mispricing—is high, at r = 0.46. Thus, an accurate option pricing model, especially one for short tenor options, must account for negative jump tail risk through NJTV as it is a significant and distinct variable from market volatility which is already factored into traditional arbitrage-free models. While the authors note that they lack the empirical data to explain the underlying economic reasons for NJTV’s significance, carrying over previous assumptions about option market demand dynamics may provide economic explanatory power.

Recall that because option markets are zero net supply markets, they are driven primarily by demand dynamics. In negative net demand markets like individual U.S. Equity Options, Li and Zhang (2011) demonstrate that the sign for illiquidity premia is positive. In these markets, market makers are net long and generate positive expected return by quoting a larger effective spread which forces net-selling end-users to accept the cost of selling options for less than full value. However, in a positive net demand market, because market makers are net sellers, the correlation between illiquidity and expected returns becomes negative, implying the existence of illiquidity discount—or in other words a liquidity premia. Liquidity premia create tighter effective spreads but also imply elevated options prices so that end-users, who are net buyers, compensate market makers for accepting the risks of being net option sellers.

When Andersen, Fusari, and Todorov (2017) found a large and consistent difference in accuracy for short tenor option pricing between a model which incorporates implied tail risk jumps and one that does not, they discovered evidence of liquidity premia on Weekly options and thus SPY Triplex options. The end-users of SPY Triplex options are net buyers who desire to reap the main benefit of short tenor options: cheaper tail risk hedging. Market makers very willingly accept the provision of Triplex on SPY because they understand that these contracts are in net positive demand for specifically hedging short-term tail risk, and so they embed the implied tail risk jump distribution into option liquidity premia. The main difference between offering only Weeklies (which were the subject of the Andersen, Fusari, and Todorov study) and offering Triplex is that in environments with immense liquidity like SPY’s, the addition of Monday and Wednesday expirations grants market makers even cheaper delta-hedging costs due to shorter lifespan, and market makers simply have more opportunities to make markets and thereby generate revenue. Because Triplex also benefits end-users by granting more flexibility and precision in creating complex hedges, it’s a win-win situation—but not without cost. The price the end-users must pay for Triplex is the liquidity premia.

Conclusion

Options carry intricate risks that no other financial instruments do, and as such, market-makers are compensated for providing option liquidity by enforcing either illiquidity premia or liquidity premia, depending on the sign of net demand within the given option market. Unlike within most US equity option markets, SPY Triplex options possess liquidity premia due to their heavy use as flexible and liquid hedging instruments. Triplex on SPY can be seen as a rare instance of the overprovision of liquidity in options markets in which liquidity premia is arbitrageable by means of short-term gamma collection, thus emulating the positioning and positive expected return of market makers. However, continued future research must be done on the Triplex phenomenon. Research on short tenor options in general is extremely sparse, but the literature will expand as additional expirations are gradually implemented onto other index-tracking names, and then eventually, non-index-tracking names, in the hopes of creating more complete and efficient options markets. When these events occur, there will be sufficient empirical data to test the validity of liquidity premia on all names that provide Triplex.

References

Andersen, Torben G., Nicola Fusari, and Viktor Todorov. "Short‐term market risks

implied by weekly options." The Journal of Finance 72.3 (2017): 1335-1386.

Chicago Board Options Exchange [1]. “Cboe History.” CBOE.com.

Chicago Board Options Exchange [2]. “Cboe Symbol Dir Weekly Options.” CBOE.com.

Christoffersen, Peter, et al. "Illiquidity Premia in the Equity Options Market." The

Review of Financial Studies 31.3 (2018): 811-851.

Crigger, Lara. "Why ‘SPY’ Is King Of Liquidity.” ETF.com, April 08, 2019.

Garleanu, Nicolae, Lasse Heje Pedersen, and Allen M. Poteshman. "Demand-based

Option Pricing." The Review of Financial Studies 22.10 (2008): 4259-4299.

Li, Gang, and Chu Zhang. "Why are derivative warrants more expensive than

options? An empirical study." Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis

(2011): 275-297.

Securities and Exchange Commission [1]. “Notice of Filing and Immediate

Effectiveness of Proposed Rule Change to Expand the Short Term Option Series Program.” Release No. 34-78695; File No. SR-NASDAQ-2016-122, August 26, 2016.

Securities and Exchange Commission [2]. “Notice of Filing and Immediate

Effectiveness of Proposed Rule Change to Expand the Short Term Option Series Program.” Release No. 34-82700; File No. SR-ISE-2018-13, February 13, 2018.